The criminal record conundrum

There probably is not a single Polish detective that has not been asked (again and again and again) about obtaining criminal records on a new hire or suspected errant employee.

It’s an expected question. It makes us nervous, and it creates frustration (and legitimate worry) on all sides.

Which means it’s about time someone in this country actually broke down the issue and told you the truth.

Obtaining criminal records without a subject’s permission in Poland is illegal.

There. I said it. And it’s illegal just about everywhere else in Europe.

Yes, I said that too. Now let’s get to how many detectives have accomplished this very task, why you do not need this or want such records—and what you actually do need to make smart hiring (and firing) decisions.

First, the dark side of the trade. For years I watched legitimate detective agencies that lost clients to “fixers,” who sometimes were not detectives at all. It was common knowledge that such fixers paid off cops or officials to gain access to police records and… ta da, criminal records and all kinds of other records, such as real estate assets or vehicles were revealed for mere pennies.

This was conducted on a widespread scale—and these kinds of activities led to arrests and charges filed on an equally widespread scale only last year, with scores of detectives now having faced license suspensions and criminal charges.

Were the 2018 arrests fair? Not particularly. Many detectives were dragged into serious charges due to an out –of-control subcontractor who paid off cops on a seemingly daily basis, but the underlying problem was there: much of the industry traditionally morphed out of former police and secret service officials used to easy access through buddies only too eager to make the odd hundred zlots.

Which leads us to the relatively chronic issue: clients, educated by years of low-level crime—if we can call paying off cops low-level—continue to request criminal histories (and more) even when told this is not accessible. So what’s to be done? Most legitimate detectives I know do not even want to receive such requests, but they are a fact of life.

Which turns us back to more education—as in why such histories are basically useless. And what you really need in their place.

So let’s talk about what you will likely receive if you manage to find a “detective with connections.” This can be a variety of “notes,” sometimes typed out but with no heading or source or really anything, or the information will be transferred orally. Which does mean you know. But clients that have arrived with said knowledge 1) have little means of using this if at all and 2) have no idea if there is any truth behind the “report.”

Perhaps this is enough. If you are worried about a new hire and you trust said detective, maybe you do not hire.

But yet there is another issue. If you do receive actual records, this means you are in possession of illegal information. Second, you are only likely to receive information on convictions over the past five years. As police squads and prosecutors undertake investigations all the time—and as by necessity they are kept quite secret during the investigative phase—the odds are against you finding out about any current investigations or past suspended (which technically means active) investigations that could very well be quite serious.

Yet clients continue to request information that at best will be illegal and almost certainly incomplete.

So what to do? A safe option would be to request that the subject visit the police to receive conviction records about his own person. This is quite doable and does not take a great deal of time. Will it be missing information about ongoing investigations and suspended investigations? Yes it wil, but this is a safe play that checks of boxes.

We would recommend prior to this, however, a quiet and highly discreet HUMINT (human source) investigation on the subject to determine reputation, links to politically-exposed-persons (PEPs) and key background points. What can be found out from former business partners, suppliers, exes and the like is typically quite illuminating, and even certain hard-copy document pulls (and there are a few to do) can incidentally include requests from prosecutors and judges for further information (which is a clear tipoff and/or launching pad for more HUMINT).

Moreover, such information can very well be admissible (although it is best to inform your detective of your intel needs going in).

Does such an investigation cost more? Yep. But remember: you do get what you pay for—and often HUMINT is the only reliable method to establish facts. Especially in these dying days of journalism, but more on that in the next blog.

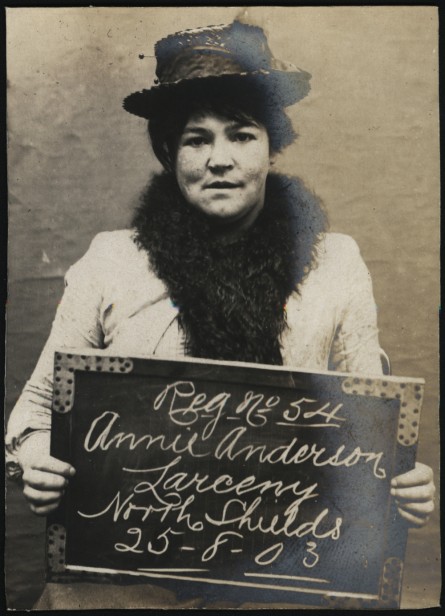

File photo of Annie Anderson's booking courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Wear Archives & Museums [No restrictions].